by Kerstin Fest

In the theatre we encounter stories, first and foremost those written by playwrights and acted out on stage. But there are also stories produced behind and beyond the stage. Gaining awareness of these secondary stories and piecing them together helps one study and understand the theatre. These background stories are especially important when studying the theatre of the past considering that the more ephemeral elements of performances, such as actors’ body language, the audience’s reaction or just the overall atmosphere in the theatre on any given evening, are no longer readily accessible. There are, however, documents that offer some insight into the complex system of the theatre. Often these documents appear in the form of lists, and these lists allow us to reconstruct the secondary stories that convert plays into productions.

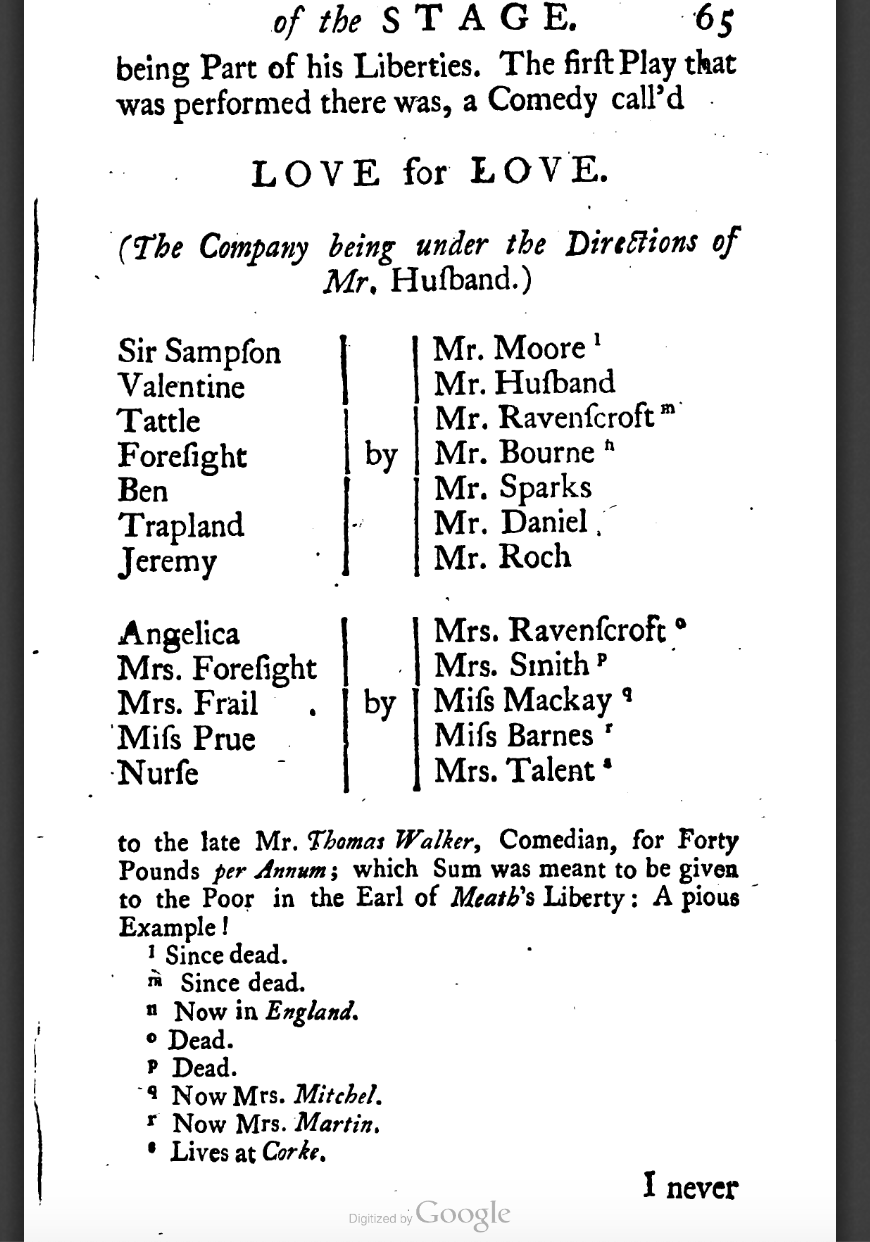

The kind of list theatre-goers and readers are most familiar with are probably dramatis personae and cast lists. For readers of a play, a list of characters preceding the main text offers orientation, a way to know what to expect and a resource to refer back to when plots get too convoluted. Character lists offer theatre-goers additional benefits when supplied in a playbill: as audience members settle into their seats, they have the chance to check which actors and actresses they will encounter; if old favourites will appear, if there will be faces known from films or TV, or if there might be an actor they dislike. Looking at historic cast lists we find dramatic behind-the-scenes stories: about rivalries such as David Garrick and Spranger Barry’s “Battle of the Romeos” (a twelve-night parallel run of Romeo and Juliet in 1750 at Drury Lane and Covent Garden respectively and with Garrick and Barry as Romeo), about the celebrity status of the likes of Sarah Siddons whose name is plastered across playbills in larger letters than her colleagues’, or about the course of actors’ careers and lives as in a list published in W.R. Chetwood’s A General History of the Stage (1749). Here we get to know what had happened to cast members since they starred in Congreve’s Love for Love in 1733: marriages, deaths and moves to England and Cork.

Cast lists may allow us to trace individual actors’ and actresses’ careers, but lists also tell stories about the inanimate objects that shared the stage with them. What follows is an inventory of theatre props and stage sets stored in Drury Lane Theatre:

Volpones dress, Falstaffs new dress, Justice Shallows dress, Falstaff old dress, 2 old jacketts of Falstaf, a leopard skin, fryars gown, scholars gown, Bacchus dress, Aboans new linnen dress in Oroonoko, 12 witches dresses, Cerberus dress, boys linen, devils gowns, Butterflies, furys devils, Lilliputian dresses, 8 Amazonian dresses

[…]

Cottage and long village, Medusa’s cave & 3 piece Grotto that changes to Country house, Inside of Merlin’s cave, Hell transparent, the Sea, Oedipus cave, a palm tree, twelve pieces of breaking clouds, a desk in the Jew of Venice, the dragon in Faustus, a popes crook, a pilgrims staff, haymakers forks, a skull and bones, Hercules’ club, the shield in Perseus of looking glass.[1]

Lists imply plenitude: one needs more than one or two things to compile one. At the same time lists also imply an order that may guide us through this very plenitude and perhaps keep it from tipping over into excess. The list above seems chaotic, a cabinet of curiosities rather than an orderly system designed to facilitate the smooth and efficient running of the complex and at times unpredictable microcosm of the theatre. Yet, wading through this storage room on paper, we can work out what dramas were staged and perhaps even what these productions looked like. Here we find Falstaff, the anti-hero in Shakespeare’s Henry IV and buffoon in The Merry Wives of Windsor, and Shylock, the conflicted villain of The Merchant of Venice; Ben Jonson’s miserly Volpone; the slave Aboan from Thomas Southerne’s stage adaption of Aphra Behn’s novel Oroonoko and Marlowe’s eponymous Dr. Faustus. Other entries hint at unnamed, but at least equally fantastic characters: devils, butterflies, furies, Amazonians and Lilliputians. Places, both homely and exotic, are listed too: a cottage, a grotto, Merlin’s cave, hell, the sea and a country house.

Beyond the stories these lists conjure up – of devils, furies and Amazons cavorting in a grotto, for instance – a list of props provides information on theatrical practices. The explicit reference to Falstaff’s old and new dress, for instance, can be read as an indication that at Drury Lane at this time actors are already appearing in character-specific, maybe even somewhat historically accurate, costumes rather than contemporary clothes (which very often were the actors’ private property), a development starting in the mid-18th-century and indicating the shift to the more ‘realist’ aesthetics taking over the stage.

The list of stage sets is proof of the extravagant visual effects, the product of rapidly developing technology on stage and beloved by an 18th-century audience. An account of the first night of Handel’s opera Atalanta published in the Daily Post on May 13 1736, shows how these random inventories of stage settings could be employed.

The Fore-part of the Scene represented an Avenue to the Temple of Hymen, adorn’d with Figures of several Heathen Deities. Next was a Triumphal Arch on the Top of which were the arms of their Royal Highnesses, over which was placed a Princely Coronet […] At the further End was a View of Hymen’s Temple, and the Wings were adorn’d with the Loves and Graces bearing Hymeneal Torches, and putting Fire to Incense in Urns, to be offered up upon this joyful Union. The Opera concluded with a Grade Chorus, during which several beautiful Illuminations were display’d.[2]

Studying theatre is

often marked by a tension between page and stage. Scholars working in Theatre

and Performance Studies are naturally more interested in theatre practice,

stressing the centrality of bodies and space for the theatre. People working in

traditional literary studies obviously focus on the text. Both camps are

somewhat hampered by the inaccessibility of the (theatrical) past. The lists

quoted above might remedy this dilemma: by drawing

together texts, spaces, bodies, performances and lives,

they tell stories and might give us at least a fleeting impression of the

confusing, intricate and colourful microcosm that is the theatre.

[1] Theatrical Collection by James Winston, manager of Drury Lane Theatre. British Library. Add. MS 38607.

[2] Daily Post, May 13, 1736.

Leave a comment