by Nick McKelvie

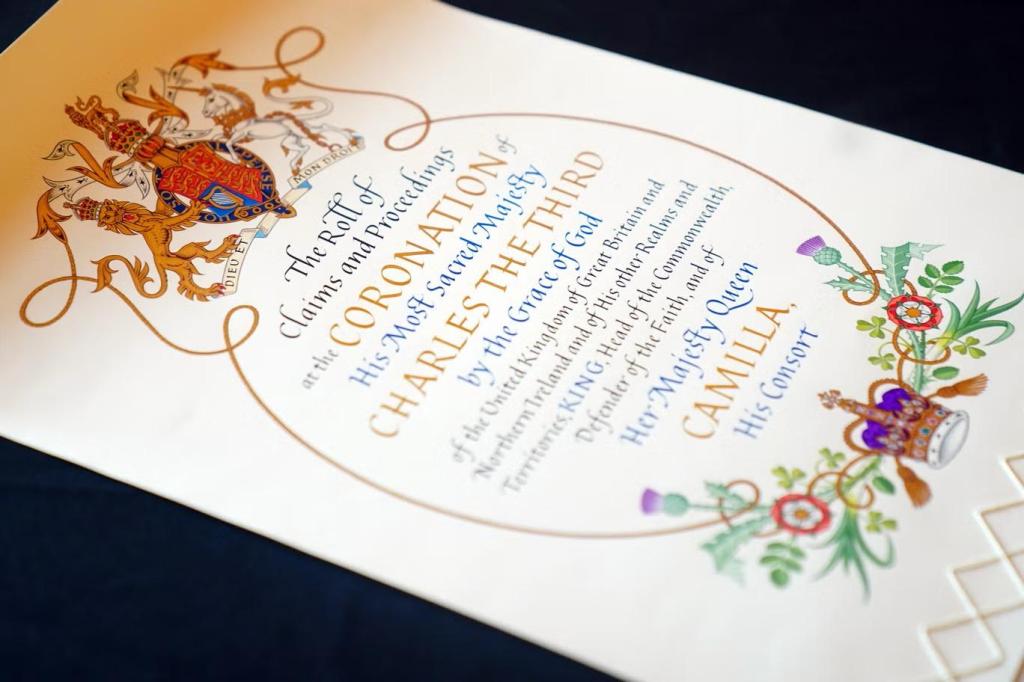

The recent coronation of King Charles III has brought new attention to English coronation traditions, including the use of a “coronation roll” to document the details of the accession. The National Archives of the United Kingdom recently announced an exhibit, for example, titled “Happy & Glorious: Coronation Commissions from the Government Art Collection,” which displays the earliest coronation roll still in existence (produced for Edward II in 1308) paired with the recent coronation roll created for King Charles III.1 Edward II’s roll is only two feet long, whereas Charles III’s is twenty-one meters; more scandalously, while Charles III’s features Queen Camilla quite prominently, Edward II’s makes no mention of Queen Isabella, although it does reference Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall, who was rumored to be the king’s lover.

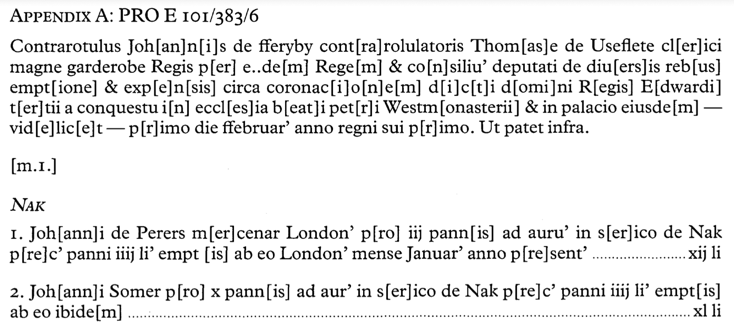

Despite their differences, both rolls essentially serve as lists of the important people, procedures, and objects involved in a coronation, and in the words of Sean Cunningham, the head of medieval records at the National Archives, they serve as “the ultimate public records.”2 It can be fruitful, however, to look beyond these celebrated accounts of pomp and ceremony to find humbler, lesser-known documents that can give a more grounded, material sense of such occasions. One such obscure but revealing document is the list of textiles purchased for the coronation of Edward III in the counter-roll of John de Feriby, 3 which provides a window into how displays of opulence driven by orientalist desires were central to England’s developing sense of itself as a world power.

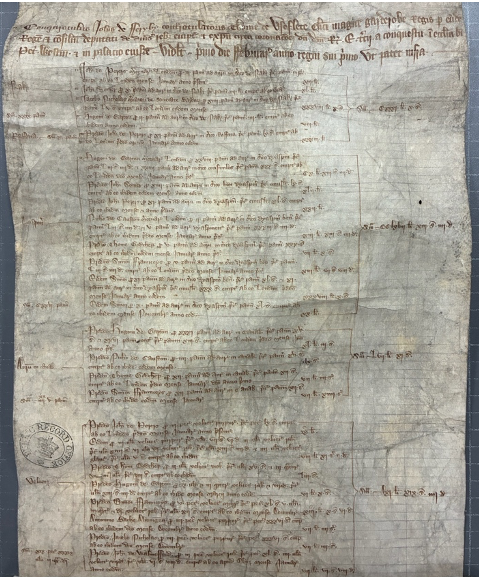

While Edward II’s coronation roll is prominently and publicly displayed at the National Archives, the Feriby counter-roll (Kew, The National Archives, E 101/383/6), derived from the accounts of the Clerk of the Great Wardrobe Thomas de Useflete, can only be accessed by special request. Just as Edward II’s coronation roll is the earliest such document still in existence, this 1327 account of the purchase of textiles for the coronation of his son, King Edward III, is the earliest surviving list of the furnishings used in an English coronation. Transcribed by Lisa Monnas in her monograph Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III, the counter-roll illustrates how the king and his courtiers sought to use cloth to convey wealth, power, and international influence visually.6 The textiles on the list are predominantly of foreign origin, as indicated both by the names used to describe them and by the list of merchants who brought them to London, and they are for the most part rich silks that originated in the Middle East and the Mongol Empire, with some coming from Italy, which had recently developed its own silk industry. The list points to a global flow of trade in which wealth was equated to sartorial luxury and foreign styles were seen as constituting, rather than contradicting, displays of English identity. Feriby’s counter-roll reveals that, from its very earliest records, the English crown was deeply invested in using non-English objects to assert power in the guise of an itinerary of exploration and to proclaim the sovereignty and global influence of its new king by appropriating, and ultimately domesticating, rich textiles.

Unrolling the Textile List

On the 1st of February 1327, Edward III was crowned the King of England in Westminster Abbey, the result of a hastily-planned but lavish ceremony that saw the 14-year-old prince installed in place of his father, who had been forced to abdicate by Queen Isabella and her allies just a week before (and who was then allegedly murdered the following September).7 The textiles purchased for the coronation are documented in a roll made up of three membranes, just under 1.5 meters long (in other words, longer than the coronation roll itself). After a brief description explaining the purpose of the account, Feriby used brackets to visually organize the cloths into groups, which were identified by name in the left margin. Within those groups, he then listed each cloth purchase, including the name of the supplier, a specific description of the textile, month of purchase, length, and price. In the left margin at the bottom of each group, Feriby calculated the total number of such cloths, and in the right margin he wrote the total cost. While this gives a sense of the value of the textiles listed, it is impossible to compare them directly because the exact dimensions of each cloth are not given.

The left margin (click image and text for larger views) prominently identifies the textiles as nak, raffata, diasper, auru in canab, velvett, samitell, camacas, Tars’, taffat’, and cindon afforc’, all of which were of foreign make, and concludes the list with the domestically produced tapet (tapestry) and pann de candlewikstret (cloth of Candlewick Street, or wool). One of the costliest textiles on the list, nak was a brocade silk “known variously as nak, nacco, nassik or nachetto” throughout Europe, and it was often imported to Italy from the Middle East or the Mongol Empire.8 Another prominently featured textile is that of Tars’, which may have been similar to nak, but with a name suggestive of either Tarsus, a city of Cilician Armenia on the Mediterranean, or panni tartarici, a term used throughout Europe to refer to “Tartar cloths” (or “Tartar silks”), which Anne Wardwell of the Cleveland Art Museum explains were drawloom textiles made of silk and gold thread.9 They were typically produced in, or traded by, the Mongol Empire, which Europeans often referred to at the time as “Tartary.”10 These names, then, typically functioned less as a description of the features of the cloth than as a gesture toward an exotic locale.

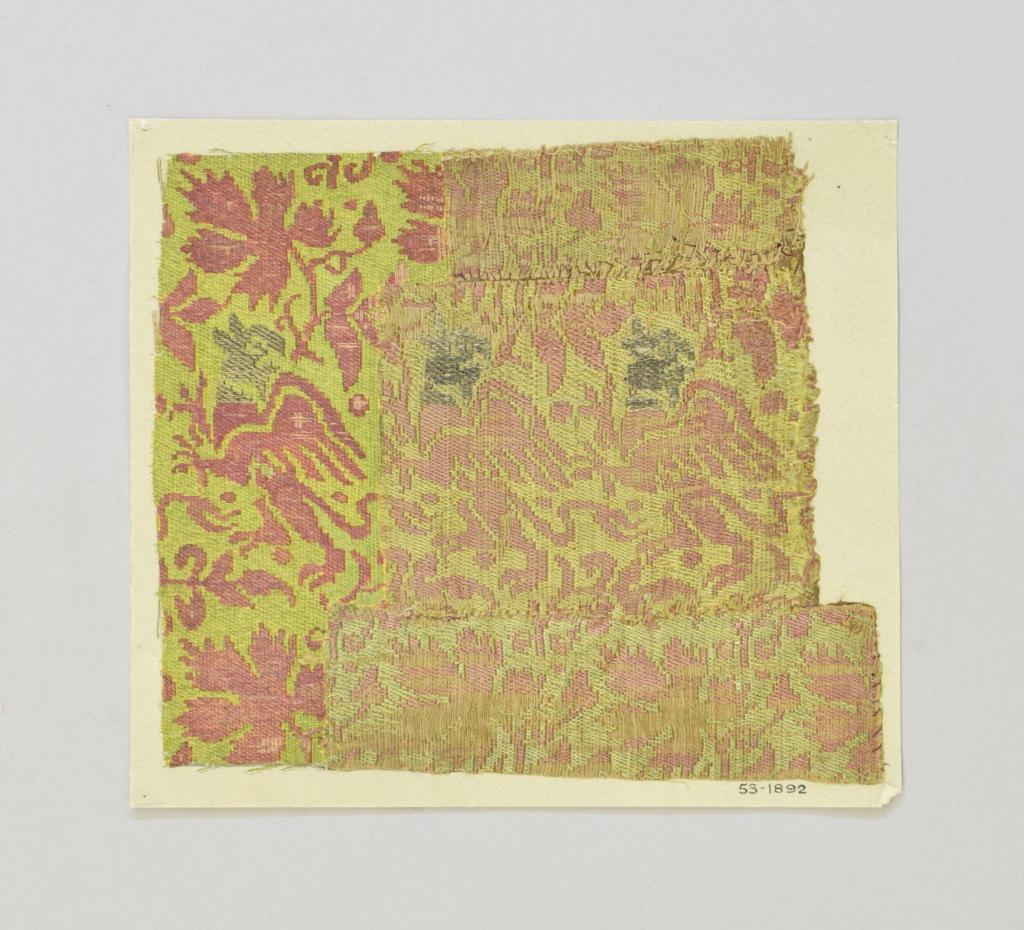

The list also enumerates several types of cloth that Europeans had recently begun producing domestically. For example, diasper—a monochrome or two-color silk typically woven with designs of beasts and birds in gold thread on a white background—may have originally been produced in Syria, but at this time it was also woven in Lucca and Venice.11 Similarly, camacas, a silk like diasper that was often woven with vines and birds,was originally sold in China and Constantinople, but by the early fourteenth century, it was also being produced in Lucca. Wardwell claims that camacas was an early example “of European silks showing the stylistic influence of Tartar silks presented in a European idiom.”12 By this time, then, Europeans not only valued Eastern textiles themselves, but had begun to adopt their designs in their own silk production. Monnas further speculates that “the adoption by Italian silk merchants of the orientalizing term camacas . . . formed part of a repackaging of . . . silks woven with ‘Tartar’-inspired designs, a marketing ploy designed to appeal to the European nobility who were then avidly purchasing ‘Tartar’ silks.”13 In a practice that is clearly visible in the Feriby counter-roll, European nobility were driven by an orientalist fascination with “Tartar cloths” to engage in what Maria Ludovica Rosati argues was an appropriation of the cultural significance, style, and materiality of Eastern textiles. As she says, “[t]hrough their material splendor,” rich textiles demonstrated “the superior condition of their owners, according to a practice of using silk typical of the whole EuroAsian continent and shared also by the Christian West since the early Middle Ages.”14 Rosati also claims that, as part of this practice of using cloth to express power and centrality in global trade, the name “Tartar cloth” was “an invention, a sort of hypernym comprising several different Asian products, a descriptive category used to bring exotic objects into the scope of the known, the familiar and the identifiable.”15

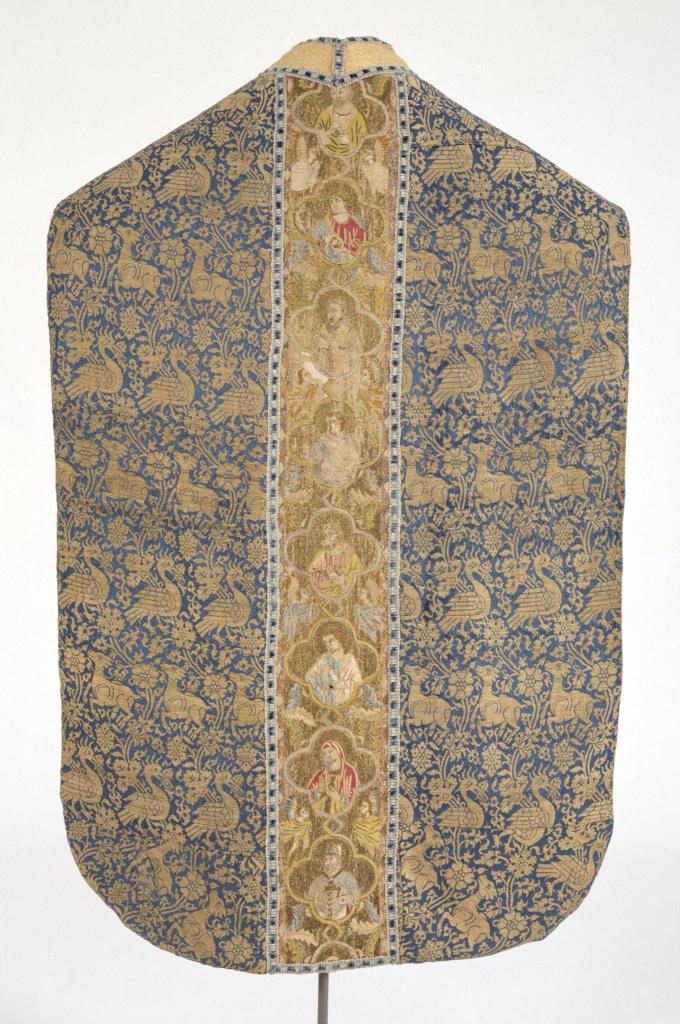

When it comes to bringing exotic silks (click on images for larger views) into the “scope of the known,” the reign of Edward III marked an important turning point in England. Rich English embroideries had long been renowned throughout Europe as opus anglicanum (English work), but the embroiderers (usually women) had always used imported silk thread and cloth, such as in the Clare Chasuble, which was commissioned by Margaret de Clare in c. 1272-1294 and was embroidered in London using silk and cotton from Iran.19 There is evidence, however, of a nascent English silk-weaving industry in England during Edward III’s reign, such as a 1368 complaint made by a group of “silkwomen” to the Mayor and the King claiming that a certain Lombard merchant was buying all the raw silk of London, thereby raising prices.20 The Feriby counter-roll, then, represents a moment when silks were still exotic but being produced (though still orientalized for marketing purposes) by Italian merchants, and when England was on the cusp of its own attempt to domesticate silk weaving.

Indeed, even the names of the fourteen suppliers listed are revealing, as they indicate how embedded they were in London. Most of the traders were, in fact, English, with only two being foreign: Anthony Bache was Genoese and Jacobo Nicholas was a member of the Bardi company of Florence. Even still, both of these foreign traders were well-established in London; in other accounts, Bache is referred to as “King’s merchant,” and he was later granted an annual stipend, while Nicholas lent money to the English crown, exported English wool, and imported jewels for Edward III’s later marriage.21 The inclusion of these extensive details demonstrates how concerned the English monarchy was with the minutiae of the textile trade, in which it aspired to become a more central player. Within this context, the counter-roll’s list of textiles and the various terms used to describe them serves as a map of the English imaginary of the world, shaped by the material culture it sought to know, lay claim to, and appropriate by producing itself.

A LOCAL ITINERARY IN CLOTH

Upon the completion of its list of textiles and its implicit map of the world, the Feriby roll then explains how each cloth was used in the coronation ceremony, laying out the itinerary of the king through his crowning, with textiles accompanying him at every step of the way. This journey began with the king’s bath early in the morning at Westminster Palace, for which four cloths of gold were issued to form a canopy over him.22 He would then have been clothed in new robes—though this account does not list textiles used for these clothes—before walking barefoot from his chamber to his enthronement in Westminster Hall and finally to his coronation in Westminster Abbey. His bare feet never touched the ground because of the domestically produced candlewikstret carpet lining the whole way.23 This wool fabric was so-named because it was made on Candlewick Street (later Candlewright Street), which, according to John Stowe’s 1603 A Survey of London, was a market street on the east side of the city, originally named for its candle makers. Stowe, an Early Modern antiquarian, also explains that the street became the residence of “diuers Weauers of woollen clothes, brought in by Edward the third” from Flanders.24 This is yet another indication of the importance Edward III’s court placed on textile production, but the presence of candlewikstret cloth in the Feriby counter-roll shows that weavers were already producing wool there at Edward’s accession. Indeed, his father, Edward II, had promoted the domestic textile industry during his reign and had banned the import of foreign textiles (with exceptions for the royal family and nobility, of course). It is true, however, that Edward III significantly expanded upon this program and started granting letters of protection to Flemish weavers starting as early as 1331.25 Stowe also notes that accounts of Candlewick Street from the early fifteenth century commented on its “cheape cloath” and specifically stated there were “no silks,” indicating that this domestically-produced wool, while useful in its own way, was seen as inferior to foreign silks.26 Little wonder, then, that panni de candlewikstret was the durable textile laid on the ground for the barefoot king to walk on.

For his enthronement in Westminster Hall, in contrast, the throne was embellished with velvet produced in Italy; cushions of samitellus that may have been woven as far away as Thebes;27 a panni adaur’ de Turk’ cloth of estate from Turkey;28 and a canopy of pannus adaur’ in canab, which was likely embroidered in England, given that it was produced on canvas.29 During the following procession to the abbey, the abbot and monks of Westminster were all decked in silk copes, which, if like those pictured below, could have been made of “Tartar cloth” or a similar textile from the Middle East and may have been embellished with either Italian embroidery or opus anglicanum. In addition, “[t]he barons of the Cinque Ports held above [Edward’s] head a cloth of silk, carried upon four silvered staves.”30

The next part of the king’s lavishly furnished itinerary took place inside the abbey, in which Edward I’s tomb was draped with a pall of diaspinus optimus cloth of gold, which was likely produced in Lucca, perhaps with design motifs evocative of Middle Eastern textiles.33 Monnas speculates that this special treatment of Edward III’s grandfather’s tomb was meant to draw attention, “amidst the scandalous circumstances of the Coronation, to this illustrious forebear.” Passing by this evocative scene, Edward III made his way to the coronation platform, or pulpitum, erected between the High Altar and the Choir and draped with “silk cloths of diasper, samitell, velvet, and Tars’,” along with “22 cloths of gold and canvas,” bringing together textiles from all over the map at the focal point of the ceremony.34

Indeed, the coronation throne itself, in the middle of the pulpitum, had cushions of camacas silk; an additional throne near the High Altar, where Edward sat for the consecration, was draped in nak (from the Mongols or the Middle East); and the High Altar was draped with Italian diasper silks and “purple velvet and striped tartar silks.”35 When Edward III arrived at the High Altar, he made an offering of a silk pall (made of dyaspinus optimus) and a gold pound, expressing explicitly the value of silk as a commodity in the ceremony of the coronation. When the king was then anointed, the bishops held a silken pall (likely the same one he had offered at the altar) over him so that he could be clothed in his royal vestments, including velvet breeches tied with purple silk, a “pallium, a magnificent square mantle displaying golden eagles” (a common design motif in both Eastern textiles and royal heraldry going back to the Roman Empire), and “a pair of new silk gloves.”36 The King then took his first steps after his anointing onto three cushions that had been recovered with cloth of Tars’.37 After the coronation, Edward III processed back to Westminster Palace in full regalia, repeating his walk on locally-produced carpet. At every step in his journey, Edward was dressed in or surrounded by textiles that spoke not just to his wealth but also his ability to acquire luxury goods from both near and far.

To the courtiers at the coronation, the textiles displayed there pointed toward exotic origins; the textiles then took part in the choreographed itinerary of the coronation route and were ultimately given out to Edward’s subjects in the aftermath of the ceremony. Some cloths were distributed to clerical and lay participants, others to Westminster Abbey, and still others were given out as alms, their value further heightened by contact with royalty.38 These furnishings, though largely foreign in their origins and often sporting designs derived from Islamic and Mongol cultures, were central to Edward’s attempts to demonstrate his legitimacy and even his Englishness.

In the recent coronation of Charles III and his consort Camilla, clothing and furnishings were once again used to express Englishness, as well as values particular to our own time. The garments used by Edward III and his contemporaries are lost to history, but those worn by recent monarchs have “changed little since medieval coronations” because they were inspired by the vestments referenced in the Liber Regalis, the first written account of the procedures of an English coronation, compiled in the 14th century.39 To visually express the continuation of the royal line, Charles wore a number of garments that had been donned by previous monarchs, but in his case he emphasized, in a statement released by Buckingham Palace, that this was also out of an interest in “durability and efficiency,” which is fitting for the eco-conscious king.40 Similarly, Queen Camilla’s robe of estate was designed domestically by the Royal School of Needlework and constructed by Ede and Ravenscroft, an English tailor, and included gold embroidery of “naturalistic illustrations,” including bees, beetles, and plants, reflective of the couple’s deep “affection for the natural world.”41

However, while the new monarchs made these sartorial design and production choices out of a desire to express modern Englishness and their personal values, some of their garments still pointed toward their “Tartar cloth” predecessors. For instance, the “Imperial Mantle,” the same type of garment that is called the “pallium” in the Feriby account, was made for the coronation of George IV in 1821 using cloth of gold and gold, silver and silk thread. While these materials and methods are similar to those used to create the textiles described in the Feriby counter-roll, the “new” Imperial Mantle was woven with a design of roses, thistles, and shamrocks, symbols that only came to be associated with English royalty (and its claims over Scotland and Ireland) centuries after Edward III. However, it does feature the fleurs-de-lis, which Edward was the first English king to incorporate into his coat of arms because of his pursuit to the French throne, and it also has golden eagles, just like Edward III’s pallium.42 That said, the 1821 mantle would not have been made of foreign silk, because, by the 19th century, England had developed an immense silk industry of its own and had long banned the import of silk. In fact, protectionist policies in the 18th century (reminiscent of those under Edward II and Edward III) led to an explosion in English silk production, to the extent that 1,100,000 pounds of raw silk were produced annually in England between 1801 and 1812, and “English merchants shipped English-made silk to America, Germany, Russia, Italy, Portugal, Holland, Ireland, and Spain.”43 The Imperial Mantle, then, is true to its name; it was made at a moment when England’s imperial power, expressed in part through its textile production, had reached its apex. By wearing the Mantle again, Charles III gestured toward England’s past, perhaps using the modern narrative of sustainability to soften the garment’s explicit imperial and colonial origins.

The Feriby counter-roll, on its own, demonstrates how humble lists of material goods can reveal the priorities of monarchs and how they were influenced by the transmission of values from other cultures. Attending to this list, with its use of orientalizing names for textiles, can help us understand how Englishness was initially defined by foreignness. The English may have feared Islamic and Mongol spheres of influence, but they also desired their luxury goods and the power conveyed by their ability to mobilize the resources to produce them.47 By incorporating these rich materials into the coronation ceremony, the English imagined that their own cultural power was as global as that of the Mongols. The historical garments of the English coronation now point backward to a time when that ambition had been achieved, when the British Empire had grown to become even more global than that of the Mongols. When the Feriby counter-roll was produced, however, it was an expression of the still rather optimistic notion that England could hold its own as a global power. As I will further explore in my next post, this aspiration for attaining power through wearing rich clothing extended even into the imaginary worlds of literature.

- “Happy & Glorious,” The National Archives, May 2, 2025, accessed May 20, 2025. ↩︎

- Caroline Davies, “Edward II’s coronation roll goes on display alongside King Charles’s,” The Guardian, May 2, 2025, accessed May 20, 2025. ↩︎

- A “counter-roll” is a copy of a roll or document used to check the accuracy of its source document. Oxford English Dictionary, “counter-roll” (n.), sense a., July 2023, accessed June 27, 2025. ↩︎

- Kew, The National Archives, C 57/1. Reproduced with the approval of the National Archives. ↩︎

- Kew, The National Archives, C 57/18. Reproduced with the permission of Press Association/Alamy ↩︎

- While Feriby’s counter-roll was partially translated in 1836, the first part of the document, which lists cloth purchases, “was deemed of such little interest that it was not included,” demonstrating how texts like this can be disregarded in favor of more celebrated accounts like coronation rolls. Lisa Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” Textile history 32, no. 1 (2001): 2. ↩︎

- W. Mark Ormrod, Edward III (New Haven: Yale University Press: 2012), 52, 55, 67. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 3. ↩︎

- Anne E. Wardwell, “Panni Tartarici: Eastern Islamic Silks Woven with Gold and Silver (13th and 14th Centuries),” Islamic Art 3 (1988-1989): 115. ↩︎

- When it comes to the name “Tartar,” Eirin Shae explains that it originated as a reference to the “Tatars,” who were one of the groups brought into the Mongol Empire by Chinggis Khan, and that “‘Tartar’ as a synonym for ‘Mongol’ during the Mongol period was applied from the outside in. That is, the Mongol khans did not refer to themselves as Tartars.” Shae further notes that, “in Latin sources, the designator Tatar or Tartar appears to have garnered associations with the term Tartarus, or hell, from early in the Mongol conquests,” which reflected “the general feelings of threat and panic the Mongol sowed as they made their way across Eastern Europe in the 1220s and 1240s.” Later in the century, that fear receded, and a hope developed, instead, that the Mongols might ally with Europeans to fight against Muslims. See Eiren Shae, Mongol Court Dress, Identity Formation, and Global Exchange (Routledge, 2020), 136, 137. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 5. ↩︎

- Quoted in Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 7-8. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 8. ↩︎

- Maria Ludovica Rosati, “Panni tartarici: Fortune, Use, and the Cultural Reception of Oriental Silks in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth-century European Mindset,” in Seri-Technics: Historical Silk Technologies, ed. Dagmar Schäfer, Giorgio Riello, and Luca Molà (Berlin: Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge, 2020), 80. ↩︎

- Rosati, “Panni tartarici,” 86. ↩︎

- Silk fragment, c. 1275-1325, diasper silk, brocaded silver, 26.5 by 55.3 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession no. 1274-1864. Accessed June 28, 2025. ↩︎

- Woven silk, c. 1175-1250, compound brocaded silk, 57.7 by 228.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession no. T.114-1998. Accessed August 22, 2025. ↩︎

- Woven silk, c. 1175-1250, compound brocaded silk, 57.7 by 228.5 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession no. T.114-1998. Accessed August 22, 2025, . ↩︎

- The Clare Chasuble, c. 1272-1294, silk and metal on blue silk and cotton in satin weave, 80 by 124 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession no. 673-1864. Accessed August 22, 2025, ↩︎

- Marian K. Dale, “The London Silkwomen of the Fifteenth Century,” The Economic History Review 4, no. 3 (1933): 324. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 3. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 12. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 12. ↩︎

- John Stowe, A Survey of London. Reprinted From the Text of 1603, ed. C.L. Kingsford (Oxford, 1908), British History Online, accessed June 27, 2025, . ↩︎

- Bart Lambert and Milan Pajic, “Drapery in Exile,” History 99, no. 338 (2014): 733. ↩︎

- Stowe, A Survey of London. ↩︎

- Known in English as samite, samitellus had a “lustrous, satin-like appearance” and was produced in both Spain and Italy, though Monnas notes that one of the samites on the textile list may have been woven at Thebes. Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 9. ↩︎

- Panni adaur translates to “cloth with gold.” Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 5. ↩︎

- In English, “cloth with gold on canvas.” Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 12. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 13. ↩︎

- Textile fragment, 14th century, woven half-silk (linen warp and silk wefts) with the design completed in watercolor, 20.5 by 18.7 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession no. 53-1892. Accessed June 28, 2025, ↩︎

- Chasuble, 14th century, tabby weave silk, silk and silver gilt embroidery on linen, 71 by 115 cm. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, accession no. 594-1884. Accessed June 28, 2025, ↩︎

- Optimus, as the name suggests,was the most luxurious (and costliest) of diasper silks. Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 5. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 13. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 16. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 18. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 19. ↩︎

- Monnas, “Textiles for the Coronation of Edward III,” 19. ↩︎

- “The Imperial Mantle, worn by King George IV, King George V, King George VI, Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III,” Royal Collection Trust, accessed August 22, 2025. ↩︎

- A.F.P., “Gold and embroidery, the ceremonial garments for the coronation of King Charles III,” Fashion United, May 5, 2023, accessed August 22, 2025. ↩︎

- Chelsey Sanchez, “The Meaning Behind Queen Camilla’s Coronation Outfit,” Bazaar, May 6, 2023, accessed August 22, 2025. ↩︎

- Jessica Brain, “Edward III,” Historic UK, November 23, 2020, accessed August 24, 2025. ↩︎

- Gerald B. Hertz, “The English Silk Industry in the Eighteenth Century,” The English Historical Review, 24, no. 96 (October 1909): 710-27, at 721. ↩︎

- Photo reproduced with the permission of Press Association/Alamy. ↩︎

- “King George V’s Coronation Supertunica, also worn by King George VI, Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III,” Royal Collection Trust, accessed August 22, 2025. ↩︎

- Photo reproduced with the permission of Press Association/Alamy. ↩︎

- This aligns with Suzanne Akbari’s assertion that “for most of [the medieval] period, the dominant power in the world was not the Christian West but rather the Islamic East, and European awareness of that inferiority played a crucial role in the development of [medieval] Orientalism.” Suzanne Akbari, Idols in the East: European Representations of Islam and the Orient, 1100–1450 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), 9. ↩︎

Leave a comment